One of the rules of thumb of genealogy is periodically review your source material to see if you spot something that you missed before. Late last week a search on Ancestry.com yielded a Confederate prisoner of war record for an M. Rutledge. So I dug out the copy of Mathew/Mass Rutledge’s applications for a Tennessee Confederate pension that I’d ordered from Tennessee a few years ago. Sure enough, I did learn something new.

We knew from a search on the NPS Soldiers and Sailors data base that Mass and his brother David (my husband’s ancestor) had served in the 16th (Logwood’s) Cavalry under Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, and that the units they served in were reorganized several times. This information was verified by the service record cards we found at Footnote.com back then. And we read about this cavalry at the time. It seemed they rode all over everywhere in western Tennessee and Mississippi.

For the life of me, I don’t know how we missed the statements that he’d been taken prisoner on Island No. 10, and had been sent to near Chicago and Wisconsin. We must not have been paying attention.

For the last four days I’ve been validating the applications, both of which were denied because the state could not verify his military service. That’s highly probable since at the time he applied the Confederate records had not been compiled. By the time Mass applied for the pension the first time, he was 76. Memories were a little faded and his handwriting was horrible. When the state wrote the US Department of War the letter had the wrong regimental information, and when they wrote for the second application, with a different regiment, Washington wrote back to see their earlier letter. Now maybe the clerk had a big pile of these verification letters on his desk, but one had to smile at this second letter given the reputation of government employees.

Mass reported he had served in the 1st Alabama, Tennessee and Mississippi Regiment Co. H., taken prisoner at Island No. 10 on the Mississippi River, spent time at prisoner of war camps near Chicago and in Wisconsin and exchanged in the fall of 1863. All 145 reels of Confederate prisoner of war records at the National Archives have been digitized and are online at Ancestry.com. Sure enough, I found record of David and Mass’s capture/surrender, transfer to Camp Douglas, near Chicago, to Camp Randall, near Madison, Wisconsin, then to Cairo, Illinois for exchange. And there was another set of service records for the 1st Alabama, Tennessee and Mississippi Infantry.

By the time all was said and done, I’d read a great deal about the campaign for New Madrid, Missouri and Island No. 10 on the Mississippi, prisoner of war camps, the fulough/exchange cartel under which David and Mass were released, and their subsequent service with Forrest’s cavalry. And why their regiments were so often reorganized. It turns out that’s one of the fastest ways to get rid of colonels and lieutenant colonels you aren’t happy with.

I was most entertained by the story told in the Osprey Men-At-Arms book, “Confederate Army 1861-1865 (5) Tennessee and North Carolina.” Apparently the Tennessee regiments of the 1st Alabama, Tennessee and Mississippi Infantry reported for duty with no weapons. Their commander ordered wooden guns cut so the troops would be able to practice the manual of arms. The regiment was eventually armed with a mixture of civilian firearms, including flintlocks, shotguns and old rifles. The commander of the cavalry regiment the Rutledges joined said it was actually mounted riflemen!

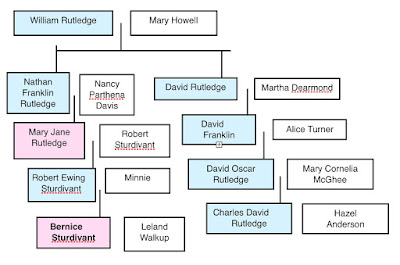

Usually people have died of natural causes, but every once in a while something unusual appears. Something tragic. Like Bernice Sturdivant Walkup's cause of death..

Usually people have died of natural causes, but every once in a while something unusual appears. Something tragic. Like Bernice Sturdivant Walkup's cause of death..